CONTACT

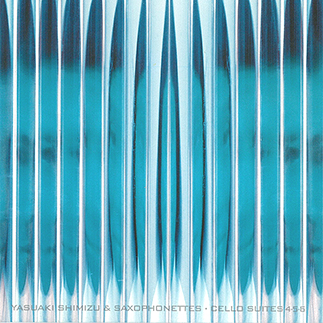

YASUAKI SHIMIZU

CELLO SUITES 4. 5. 6

CELLO SUITES 4. 5. 6

チェロ・スウィーツ 4. 5. 6

-

1Suite 1 - Prélude (第4番 プレリュード) Suite 4 - Prélude

-

2Suite 4 - Allemande (第4番 アルマンド) Suite 4 - Allemande

-

3Suite 4 - Courante (第4番 クーラント) Suite 4 - Courante

-

4Suite 4 - Sarabande (第4番 サラバンド) Suite 4 - Sarabande

-

5Suite 4 - Gavotte I, II (第4番 ガヴォット I, II) Suite 4 - Gavotte I, II

-

6Suite 4 - Gigue (第4番 ジーグ) Suite 4 - Gigue

-

7Suite 5 - Prelude (第5番 プレリュード) Suite 5 - Prelude

-

8Suite 5 - Allemande (第5番 アルマンド) Suite 5 - Allemande

-

9Suite 5 - Courante (第5番 クーラント) Suite 5 - Courante

-

10Suite 5 - Sarabande (第5番 サラバンド) Suite 5 - Sarabande

-

11Suite 5 - Gavotte I, II (第5番 ガヴォット I, II) Suite 5 - Gavotte I, II

-

12Suite 5 - Gigue (第5番 ジーグ) Suite 5 - Gigue

-

13Suite 6 - Prelude (第6番 プレリュード) Suite 6 - Prelude

-

14Suite 6 - Allemande (第6番 アルマンド) Suite 6 - Allemande

-

15Suite 6 - Courante (第6番 クーラント) Suite 6 - Courante

-

16Suite 6 - Sarabande (第6番 サラバンド) Suite 6 - Sarabande

-

17Suite 6 - Gavotte I, II (第6番 ガヴォット I, II) Suite 6 - Gavotte I, II

-

18Suite 6 - Gigue (第6番 ジーグ) Suite 6 - Gigue

1996年に発表した「チェロ・スウィーツ 1.2.3」以来、本作で無伴奏チェロ組曲1番から6番を完奏。清水は録音場所を求めて九州にある廃線になったトンネルや水力発電所、また大仏殿他数カ所に出かけ、実際にその場でサキソフォンを鳴らしてみた。その結果、釜石鉱山、イタリアのヴィラ・コンタリーニ、パラッツオ・パパファーヴァが、このアルバムの録音場所に選ばれた。その空間自体を楽器として捉える清水のアプローチは、とうとう…………..。

The sequel to his 1996 release Cello Suites 1.2.3, this album completes Shimizu’s saxophone versions of Bach’s six Cello Suites. In pursuit of the ideal acoustics for the recordings, Shimizu went to an abandoned railway tunnel, a hydroelectric power plant, a Buddhist temple and other locations to experiment with their effect on the saxophone’s sound. The album was eventually recorded in the Kamaishi mine in Japan and the Villa Contarini and Palazzo Papafava in Italy, exploring Shimizu’s concept of space as an instrument.

-

グッと来るポイント

チェロスウィーツの1. 2. 3 もそうなんですが、サキソフォン、セバスチャン・バッハ、ある空間って言うのが3点セットで、イメージ的に”グッとくるポイント”だなって、ふと感じてきまして…というのはまず、色々前の僕のコメントなんかで説明していますが、サキソフォンというのは新しい楽器で、たかが100年くらいしかたってない。それで今はクラッシック音楽、ジャズ、ロックそれから歌謡曲なんかにも適用されている。クラッシックで使われているときは意外と崇高なニュアンスがあるんですけれども、低俗なニュアンスってのが一般的だと思うんですね。そんなサキソフォンと”バッハ”というこのアンユージュアルコンビネーションていうか、それが観念的な意味の交差でもおもしろいし、直観的にもおもしろかったわけですよ。何故かって言うと、バッハに関して人々は崇高さの拠り所みたいに言ってるところがあるじやないですか。どっちかっていうと宗教に近い。崇高なものとして仏壇に飾っておく様な……。実際は僕はヨハン・セバスチャン・バッハていうのは、そういう人じゃなかったと思う。なんだろな宗教以前の、どっちかって言うと欲望肌であったと思うのね。だから社会的に出来上がった観念以前のところでサキソフォンとセバスチャン・バッハっていうのがすごくフレンドリーっていうか、手を繋ぐポイントがあると思ったのね、それで、それを行うにあたって、ある普通のレコーディングスタジオやコンサートホールで録音するよりも、壁を破って出ていく感じっていうのを打ち出したかったわけ。決められた音楽の場所じゃない、まったく音楽で使われていないような場所。周りのノイズが中に入ってきて、まあ、密閉されていない空間だよね。外部から遮断された無音の空間、ていうのがいわゆるコンサートホール及びレコーディングスタジオだよね、それは何故かって言うと、そういうところに外部の雑音が入るとその楽器に集中出来ないんじゃないかとか、その楽器の音を浮き上がらせて録音するっていう状態だよね。そういうんじゃなくて、楽器音ていうよりも、その世界を鳴らす事が出来ると思った。これも直感でね。あとから観念が付いて来るんだけどまずは直観で。最初から観念に左右されることはないですね。だから、いつも観念から入ってくる場合は、疑うっていうのが…

そういうことがあって1. 2. 3を録音する辺りからいろんな場所を下見したわけです。音だけじゃなくて、いろんな意味が丁度僕の”グッと来る感じ”に合う所っていうのを選びたかったのね。だから例えば今回の、ヴィッラ・コンタリーニっていうのは歴史的な意味でバロックと結びついているから面白いとか、そういう意味ではないわけです。実はそういう意味も批判的な意味で入ってるけど…。下見にはサキソフォンを持って、そこで演奏しながらそれぞれの場所にある文化的意味とか中の空間の視覚的デザイン、それから音の関係、あとはどういう音が周りから入ってくるか聞きます。例えば雨の音が入ってくるか動物の音が入ってくるか、それから人の話し声が聞こえたりするかとか、そういう事を意味として凝縮したのが肉体にどう関わってくるかっていうことですよね。それで初めて僕にとって”グッと来るポイント”。これしか言えないんだけど…。

-

螺旋の音楽

ヨーロッパの音楽界が挙げてホモフォニーに移行しようという時期に、J.S.バッハはあくまでもポリフォニックな音づくりにこだわっていた。主旋律中心主義のホモフォニーとはちがって、ポリフォニーにはそれぞれの音に主従関係はない。というか、音楽の流れにしたがって主役は次々に変わってゆくのだ。定義上、個々の楽音やメロディーよりも、それらの相互関係が重視されるのがポリフォニーであり、その意味で主役・脇役が固定した古典的演劇やバレエではなく、ベケット以降の演劇やモダン・バレエに近いとも言える。1番から3番までを録音した前作『Cello Suites 1.2.3』のライナーノートにも書いたことだが、バッハの『無伴奏チェロ組曲』は、単旋律の楽器でポリフォニーを実現するために、ある巧みな戦略を用いている。チェロの「弱点」を逆手に取り、分散和音によって実際には奏でられていない音を暗示し、聴く者の脳の内側にポリフォニックなハーモニーを仮想的に生じさせる、というものだ。譜面の上の音符は、ともすればひとつひとつが独立して存在しているように見えるけれど、実際には個々の音はそれぞれが豊かに関係している。どんな音楽にも共通しているはずのその事実を、バッハはオーケストラやピアノではなくシンプルな弦楽器を用いて、最もミニマルなかたちで浮き彫りにして見せた。 バッハのその戦略、あるいは作戦指令に対し、清水靖晃はふたつの戦術をもって見事に応えている。ひとつは「超絶技巧できちんと演奏する」という正攻法。もうひとつは「よく響く空間を演奏=録音の場所として選び、その空間全体を楽器と化す」といういささかアクロバティックでトリッキーな方法。そして清水の「作戦」は、バッハが予想もしていなかったであろう別の「戦果」を生み出した。一見ホモフォニック、実はポリフォニックな音の連なりを聴きながら、われわれは期せずして地下から地上へ、さらには天上へと旅することになるのだ。

1番から3番の演奏=録音には大谷石の採掘場などが用いられたが、4番から6番には、東北地方にある釜石鉱山花崗岩地下空洞(4番)、イタリアはパドヴァのヴィラ・コンタリーニ(5番)、同パラッツォ・パパファーヴァ(6番)が選ばれている。いずれも歴史的な建造物であり、音響的には残響が極度に長いのが特徴だ。 清水はこれらの意表を衝くような場所を自ら探し出し、万全の準備を整えて録音に臨んだ。「響きにひずみがあって波形が複雑な残響」と「ほどよい雑音」(いずれも清水談)を求めて訪ね歩いた場所は、廃線となった鉄道のトンネル、水力発電所の内部、研究所の反響室など国内外あわせて十指に余る。その努力は十二分に報われたと言えるだろう。 釜石鉱山には、ヘルメットを装着し、トロッコに乗って、狭い坑道を500メートルほど潜ってゆく。1829年に採掘をはじめ、1993年に役割を終えたという歴史的鉱山だ。地下には300�Fほどの広さ、7メートルほどの天井高がある「花崗岩場音響実験室」があって、ひんやりとした濡れた空気が出迎えてくれる。気温は年間を通して10~12℃。地下水のために湿度は常時90%を上回る。 ヴィラ・コンタリーニは、16世紀から17世紀にかけてヴェネツィアの貴族コンタリーニ家が建造した巨大な離宮である。パドヴァの中心部から車で30分ほどの距離にあり、堂々たるファサードや両翼、広大な敷地内の湖が、往時のイタリア貴族の権勢を感じさせて見る者を圧倒する。録音が行われたのは、アウディトリオという響きのよい部屋で、3階のキターラ(ギター)と呼ばれる部屋まで吹き抜けになっている。かつては宴の折に楽士が3階で演奏し、客の耳もとまで音楽が「降ってきた」という。 パラッツォ・パパファーヴァは1760~63年に、パドヴァの貴族ジャンバッティスタ・トレントが建てた邸宅だ。新古典主義の要素も取り入れた美しい屋敷だが、パドヴァ市の中心地にあり、現在もトレントの子孫が住む現役の住宅でもある。録音場所には250�Fの広さ、12メートルほどの丸天井(クーポラ)を備えたサロンが選ばれた。ヴィラ・コンタリーニと同様、音は互いに遊び戯れるように響きあう。

耳を澄ませば、聴こえてくるのはサキソフォンの音ばかりではない。鉱山の地下空洞からは天井から滴り落ちる微細な水の音が、郊外の離宮と街の中の邸宅からは車や飛行機の音、人の声などの生活音が、ポリフォニックな楽音の中に混ざり込んでいるのがわかるだろう。もちろん音楽家と録音スタッフは、音楽と対立するような極端なノイズを注意深く取りのけてはいる。だが、完全に外界と遮絶された、たとえばスタジオのような空間で録音された音楽とは異なり、この音楽は自分と響きあい、感じあえるようなノイズを、排除するのではなく、あえて積極的に自分の中に迎え入れている。ジョン・ケージがピアノの中に放り込んだ消しゴムのような、意図され、仕掛けられた偶然。ここでは音楽は、比喩ではなく現実に、とても量的で立体的だ。何よりも感動的なのは、音楽が地下と地上、そして天上とを往還していることだ。地下空洞には闇と冷気が満ち、結露と高い湿度があり、閉鎖的な、混沌の(アモルフアス)空間として音楽を封じ込め、支配している。パラッツォは俗世のただ中に身を置き、音を水平軸に沿って広がらせる。ヴィラには光と熱気が溢れ、乾いた風が吹き込み、開放的な、相称の(ルビ:シンメトリック)空間として音楽を天の高みに上らせる。清水のサキソフォンから発せられた楽音は、あたかもダンテの『神曲』のように、地上と煉獄、地獄と天国を経巡るのである。そしてそれぞれの場所で―地下であってさえも―内外にあるノイズと、豊かな、エロティックとも言える関係を取り結んでいる。ポリフォニックなバッハの音楽は、神へ捧げられているという意味で外部に開けている半面、技法的には内部に見事な構造を備えている。一方、清水靖晃の『Cello Suites 1.2.3』は、バッハのつくりあげた構造を尊重しつつ、それとは別の構造=関係を「内」と「外」の双方に向けてつくり出すことに成功している。「内」と「外」を、あるいは地下から地上、地上から天上を自在に走り抜けるには、螺旋形が最も望ましい形状だ。ここに繰り広げられているのは「螺旋の音楽」なのである。

(小崎 哲哉)

-

東京が精神的に疲れるところであることを否定する人はいないだろう。そういう状態に陥った時は、バッハの音楽は心のスポーツ・ドリンクのように染み渡ってホッとさせてくれるものだ。中でも無伴奏チェロ組曲は特別のマジックを発揮する作品だが、沢山あるヴァージョンの中から自分の周波数(?)に合うものを選ぶことは必ずしも容易ではない。3年前に発表された清水靖晃の「CELLO SUITES 1.2.3」(本作はその続編)を聴いてピンときた。チェロをテナー・サックスに置き換えるという発想の大胆さはまず気に入った。演奏そのものは忠実で、楽器の音域は似ているし、チェロにもテナー・サックスにも独特の色っぽさがある。そしてサックスで解釈することによってとてもコンテンポラリーな響きが出ている。バッハもあの世で納得しているに違いない。

またCDの音質も驚くほどよくて、97年に引っ越したばかりの我家で「CELLO SUITES 1.2.3」をよくかけていたが、遊びにくる友達は必ずステレオの素晴らしさについてコメントしてくれた。それは装置ももちろん悪くはないが、そういうコメントをいただいたのは「CELLO SUITES 1.2.3」が鳴っている時だけだった。

さて、「CELLO SUITES 4.5.6」だ。前作とどこが違うか。録音の一部(厳密に言うと3分の2)がイタリアで行われたことが最大の違いかな。気のせいか、バロックの匂いがより強く出ている感じがする。かな?まあ、「CELLO SUITES 1.2.3」が好きだった方は間違いなくこちらも気に入るし、こちらから聴いた方は必ず「CELLO SUITES 1.2.3」も欲しくなるだろう。 疲労した心にプレゼントのつもりで、私に騙されたとでも思って是非聴いてください。

(ピーター・バラカン)待望の清水靖晃ニューアルバム。20世紀の新たなる遺産が完成。ってナレーションが頭に浮かんだ。音楽にはいろんなジャンルや表現があるけれど、靖晃さんのは宇宙一ゴージャスでセクシーなサックス、オルゴール造りの職人か米にお城を描く名人のように気を配った緻密で緊張感の中に拡がる心地よい空間とか、ラテンやメイシオ・バーカーのようにファンキーなものまであってこのバッハに関しては20世紀最後のニューなクラシックという新しいものである。クラシックの反対語がニューでいいのか?とは思うけど。

バッハ1~3のアルバムは我が家のデスクトップCDトレイに通算で2年はいただろうか、ついに僕は次回作の映画をバッハで書いてしまった。新しいバッハからもインスピレーションを受けて書いたシーンもたくさんある。バッハその人が星を見ながら作曲したと言われている人だし、宇宙的作曲家の靖晃さんはインスピレーションだらけの天才。まさしくバッハを吹くためにも生まれてきた人なのでありましょう。

今回の楽曲は前回よりも耳にやさしく、気持ちよく昼寝が出来てしまう。おかげでデスクトップはよだれのあとだらけです。

(中野 裕之)

-

Spiral Music

At a time when music throughout Europe was poised to switch to homophony, Bach stuck doggedly to the creation of polyphonic works. Homophony focuses on the main melody. Polyphony, by contrast, is characterized by the absence of any such hierarchical relationship, and different melodies take the central role according to the flow of the music. In polyphony, then, by definition, the interplay and interrelationship of the music is regarded as more important than any single melody. Polyphony is not like classical drama or ballet—in which the major and supporting roles are fixed—but more like post-Beckett drama or modern ballet, in which lead and supporting roles are fluid and interchangeable.In the notes accompanying Shimizu’s earlier recording of Cello Suites 1.2.3 I pointed out how Bach employs an ingenious strategy to achieve polyphonic harmony with a basically monophonic instrument: Turning the very “deficiencies” of the monophonic cello to his advantage, Bach uses broken chords to suggest or evoke notes that are never actually sounded, and in doing so creates in the mind of the listener a “virtual” polyphonic harmony. Printed notes on a music score may seem to exist as independent entities, but in fact they are deeply and richly interrelated. Bach demonstrated this point in its most minimal form, by using neither the piano nor orchestra, but a simple stringed instrument.

Shimizu has risen to the challenge of Bach’s strategy with an equally brilliant strategy of his own. On the one hand Shimizu adopts an orthodox approach by simply playing with consummate virtuosity. On the other hand he shows ingenuity in selecting spaces characterized by a high degree of echo, thus turning the very space itself into a musical instrument. Shimizu’s strategy has gone on to yield results which Bach never imagined, because what initially seems to be homophonic, turns out, the longer we listen, to be polyphonic music which captures our attention and takes us on a journey from below to above ground, and thence up to the skies!

Like Cello Suites 1.2.3, Cello Suites 4.5.6 were recorded at three distinct locations: the Kakokan underground cavern in the Kamaishi mine in Japan’s Tohoku region for Suite 4; Villa Contarini for Suite 5 and Palazzo Papafava for Suite 6, both in Northern Italy. All three places are rich in history and remarkable for their acoustics, characterized by extremely long-drawn-out reverberations.

Shimizu himself tracked down these stunning locations, only venturing to make the recordings after the most exhaustive preparations. As Shimizu explains, in his quest for “sound distortion and complex echo wave patterns” and “just the right degree of atmospheric noise,” he visited over ten places both in and outside Japan, including a disused railway tunnel, the inside of a hydroelectric power station, and the echo chamber of a research institute. As these recordings show, his labors were to pay off handsomely.

The Kamaishi mine opened in 1829 and only ceased its mining operations in 1993. Wearing a hard hat, a little handcar takes you 500 meters into the mountainside through a narrow tunnel, before you are greeted by the cool, damp air of the Kakokanjo Acoustic Laboratory – a space of 300 square meters with a 7 meter-high roof. Here the temperature stays between 10 and 12 degrees centigrade all year round, while groundwater keeps the level of humidity at over 90 percent.

Villa Contarini was built in the course of the 16th and 17th centuries by the Contarinis, a Venetian aristocratic family. Situated 30 minutes’ drive from Padua, the Villa’s magnificent winged facade and vast lake in the grounds give the viewer an overwhelming impression of the power of the Italian nobility during those times. The recording was made in the auditorio, a room with excellent acoustics, and which features an opening in the ceiling connecting the auditorio to the chitarra (guitar) chamber on the 3rd floor. Here, musicians used to perform, and the music would float down for all the guests to hear below.

Palazzo Papafava was built by the Paduan aristocrat Gianbattista Trento between 1760 and 1763. Located in the center of Padua, this splendid mansion, partly neo-classical in style, is still lived in by the descendants of Trento. The space chosen for recording was a 250 meter-square drawing room with a rounded cupola ceiling 12 meters high. Here, just as in the Villa Contarini, sounds reverberated and intermingled in playful fashion.

If you listen carefully to the recordings, you will be able to hear more than just the sound of the saxophone. In Suite 4 you can discern the sound of minute drops of water dripping from the roof of the Kamaishi mine, while in the Villa and in the Palazzo of Suites 5 and 6, the sounds of everyday life—cars, airplanes and voices—are mixed deep within the polyphonic tones. Shimizu and the recording staff naturally made sure that any extreme forms of noise were excluded if they conflicted with, rather than enhanced, the music. Nonetheless, unlike studio recordings made in a space hermetically sealed off from the outside world, the music here—far from rejecting noises and sounds that have resonance for us and with which we empathize—chooses instead to welcome and incorporate them. This is the music of “planned chance,” as when John Cage flung an eraser into a piano. It is full-bodied and three-dimensional in the most literal sense.

Most moving of all is the way in which the music progresses from subterranean depths to above ground, from there soaring skywards. The underground cavern in the mine was dark, cold, dew-drenched, humid, a chaotic, amorphous space that shut in and subjugated the sound. In the Palazzo, set amid the bustle of everyday city life, the music was able to spread out along the horizontal axis. The Villa meanwhile was architectural symmetry itself—a delightful place, full of light, heat and a warm dry breeze where Shimizu’s music soared. In this way, like Dante in The Divine Comedy, the notes that spill out of Shimizu’s saxophone travel through earth, purgatory, hell, finally reaching up to heaven. And at each location—even below ground—a subtle bond with incidental noise comes about, a bond that is rich, profound, one might even say erotic. In the sense that Bach’s polyphonic music is consecrated to God, it is externally focused and open. Paradoxically, its technical structure is internally focused and closed to an astonishing degree. Shimizu’s interpretations of the Cello Suites, while respecting the musical structures created by Bach, also succeed in forging a new connection to link the internal and the external. The idea of traveling freely through the internal and the external, from below to above ground, or from above ground to the skies, might ideally be represented as a “spiral.” This is why I chose to call this interpretation of the Cello Suites “spiral music.”

— Tetsuya Ozaki (translated by Giles Murray)

-

Few people would contest that Tokyo is a stressful place. When the city gets to you, a bit of Bach can soothe the soul the way a sports drink rehydrates the body. Of his oeuvre, I find the Cello Suites particularly magical, though I couldn’t readily say whose interpretation best suits my wavelength. That is, until I first heard Yasuaki Shimizu’s Cello Suites 1.2.3 three years ago. I was immediately taken by the exuberance of his idea to use the tenor sax in place of the cello. His playing is faithful and the sax resembles the cello, though each instrument possesses a unique sensuality. And the sax lends the scores a contemporary flair that I’m sure Bach, in the other world, would appreciate.

The quality of sound on this CD is unbelievably good. When I moved home in 1997, we played it a great deal. Friends always asked after the great quality of our stereo. Of course, my system is not at all bad, but the comments were always forthcoming when Shimizu’s CD was playing.

And now, Cello Suites 4.5.6. Where does it differ from the previous CD? The fact that a portion of the recording (two thirds) took place in Italy is possibly the biggest difference. Perhaps it’s just me, but this one feels more baroque. Anyway, for those who liked the first CD, they’re bound to want Cello Suites 4.5.6. Even if you think I am pulling the wool over your eyes, please listen to this CD when your soul is feeling tired.

— Peter Barakan, music critic/commentatorThe long awaited new album by Yasuaki Shimizu. A new 20th century legacy is consummated. Well, that’s the narration I heard in my head. Granted there are many musical genres and expressions, but Yasuaki is the sexiest saxophonist in the world. Like a music box craftsman or a miniaturist who paints castles on rice, he creates a place of wonderful sensations out of the tension of sensitive, meticulous work. With elements from Latin to funky, Yasuaki’s Bach may be this century’s last new music or “new classical.” Wouldn’t the antonym classical be new? At least I think so.

Shimizu’s Cello Suites 1.2.3 remained in the family CD player for a total of two years. I wrote the scenario for my next film while listening to Bach, and many scenes were directly inspired by this “new” Bach. Bach himself is reported to have composed while stargazing and cosmic composer Yasuaki is a genius bursting with inspiration. Surely, he was set on Earth to play Bach. The new compositions are even lovelier to the ear than the last, lulling me into delicious deep naps. Thanks to this, my desktop is a puddle of drool.

— Hiroyuki Nakano, film director

プロデューサー: 清水 靖晃、内田 英樹

作曲: J. S. バッハ

清水 靖晃: テナーサキソフォン

レコーディング: 叶 眞司

プログラミング: 保坂 城太

録音場所:

第4番: 釜石鉱山花崗岩地下空洞(岩手県釜石市)

第5番: ヴィラ・コンタリーニ(ピアッツァオーラ スル プレンタ、イタリア)

第6番: パラッツォ・パパファーバ(パドヴァ、イタリア)

Produced by Yasuaki Shimizu, Eiki Uchida

Composed by J.S. Bach

Yasuaki Shimizu: tenor saxophone

Recorded by Shinji Kano at:

Suite 4: Kamaishi Mine, Kamaishi (Japan)

Suite 5: Villa Contarini, Piazzola sul Brenta (Italy)

Suite 6: Palazzo Papafava, Padova (Italy)